Most of us see autumn as the real new year, involving a return to life and a reignition of things. A good time to step aside the fray and consider what propels you. We’re in a history-rich time, not a thin one, and restating your premises can be reorienting.

Some of what drives this column is a belief that reading history—bothering to know it and reflect on it—is good. Remembering its helpful and even inspiring parts is constructive, not sweet. Seeing and naming various current deteriorations isn’t reactionary or nostalgic and can function as at least an attempt at correction.

This summer I read the historian David McCullough’s 1995 speech accepting the National Book Foundation’s highest honor, the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. It constitutes the brief first chapter of “History Matters,” a collection of McCullough’s essays, interviews and speeches, out this month from Simon & Schuster. Collections that include some previously unpublished work (McCullough died in August 2022) can have a barrel-scraping feel but this one doesn’t—its seriousness and simplicity reflect the author and make for beauty. At the time of the address McCullough had written “Mornings on Horseback,” “Truman” and “The Johnstown Flood”; “John Adams,” “1776” and “The Wright Brothers” would follow. There couldn’t have been a worthier recipient.

Why does history matter? “History shows us how to behave,” McCullough begins. “History teaches, reinforces what we believe in, what we stand for, and what we ought to be willing to stand up for.”

It is not only the dry recording of facts, it has a moral quotient. “At their core, the lessons of history are largely lessons in appreciation.” Everything we have, he says, all the great institutions, the arts, our law, exists because those who came before us built them. Why did they do that? What drove them, what obstacles did they face, how are we doing as stewards and creators? “Indifference to history isn’t just ignorant, it’s rude.” This is a wonderful sentence because it is true and bluntly put. Ignorance is a form of ingratitude.

History encourages “a sense of proportion about life,” gives us a sense of scale. “What history teaches, it teaches mainly by example.”

To live in an era of momentous change and huge transitions is to experience great pressure. Knowing history, reading it, imparts “a sense of navigation,” a new realization of what we’ve been through and are made of. Those who came before us were tough: “There’s no one who hasn’t an ancestor who went through some form of hell.”

In the end, knowing history “is an extension of life. It both enlarges and intensifies the experience of being alive.”

McCullough looms large in my life both as professional whose work I could aim my arrow at, and as spur. I would hear from him when a column spoke to him. After one mentioned the importance of great formal ceremonies marking the passing of the famous dead, he wrote to say yes, such things, “remind us of our dignity.” That dignity, which he sensed and portrayed in his work, and which he knew was aligned with and not poised against finding the truth, was important to him.

Here I jump to an aspect of this column, which is the importance of what was.

Earlier this summer I wrote that we now routinely say and do things in our public life that are at odds with our history, that are unlike us. I focused on President Trump’s language and imagery when speaking to the troops at Fort Bragg, N.C., in early June. His remarks were partisan in the extreme, even for him; it was a Trump rally, not a president addressing the troops. Elsewhere, on sending the National Guard into Los Angeles: “When they spit, we hit.” All of it, the rally and what he said, was, I said, the kind of thing we don’t do. And we mustn’t lose sight of what we don’t do.

Soon after I got a note from a veteran political consultant who’d prospered in both the old political world and the new. He wanted me to know he “agreed with every word.” He then explained with some patience and yet a kind of proud shame that things have changed: “Today people like me raise money and put activists on the payroll to pour kerosene on the fires they ignite.” Protests in the previous political era were organic and natural. “They are now a division of political campaign structure.” The young people he works with know no other reality. “I’m saddened that the political world I have in some part helped construct has come to this.”

He was trying to help me: I had perhaps not noticed our politics had become increasingly malevolent. I replied that I knew quite a bit of what he and his colleagues on both sides are up to, and that as I work I often have the young of politics and media in mind. I am trying to tell them something, to give them a template. I said it is our job, in our generation, to bring the sturdier public values of the recent and distant past into the current moment. We have to put forward those ways from the past that helped, that were superior, or no one will know they existed. And no one will be able to imitate or absorb or reflect them.

“I write for those 33-year-old operatives you speak of who have actually never seen grace.” If they don’t know what it looks like they can’t emulate it, they can’t adopt it and give it new life because they don’t know what it was.

What I didn’t say but meant: When you see a decline in public standards that were once fairly high, when you see our public life become rougher and uglier, you can accept it, even go with it, or you can fight, you can push hard against what’s pushing you, as Flannery O’Connor put it.

And what I’m saying is this is our way of pushing hard. McCullough might say it’s ungrateful not to.

You can’t be dreamy about the past and say, “It was nice then.” It was never nice, it was made by human beings. You can’t say, “People were better then.” They weren’t. But in even the recent past the allowable boundaries of public behavior were firmer, and the expectations we held for our leaders higher. And their public behavior (not private, or not necessarily private) was often preferable to the public behavior we see today. So you don’t want to live in the past, but you do want to bring the best of the past into the present.

History goes only one way, forward, and the history we’re living won’t be getting less rough with time. Neither will our political manners. Neither will the strains under which we are put as a society and a political culture.

But my generation owes those who follow more than “Here’s some cash,” “Toughen up” and “Get off my lawn.”

It’s hard to think of anything more helpful as the new year begins than reading history, spying out the moments of dignity and grace, seizing them and trying to pull them into the future.

But all sorts of feature reporting puts AI higher up. Last week Noam Scheiber in the New York Times reported economists just out of school are suddenly having trouble finding jobs. As recently at the 2023-24 academic year, said a member of the American Economic Association, the employment rate for economists shortly after earning a doctorate was 100%. Not now. Everyone’s scaling back, government is laying off, big firms have slowed hiring. Why? Uncertainty, tariffs and the possibility that artificial intelligence will replace their workers. Mr. Scheiber quotes labor economist Betsey Stevenson: “The advent of AI is . . . impacting the market for high-skilled labor.”

But all sorts of feature reporting puts AI higher up. Last week Noam Scheiber in the New York Times reported economists just out of school are suddenly having trouble finding jobs. As recently at the 2023-24 academic year, said a member of the American Economic Association, the employment rate for economists shortly after earning a doctorate was 100%. Not now. Everyone’s scaling back, government is laying off, big firms have slowed hiring. Why? Uncertainty, tariffs and the possibility that artificial intelligence will replace their workers. Mr. Scheiber quotes labor economist Betsey Stevenson: “The advent of AI is . . . impacting the market for high-skilled labor.”

But I think Butler may loom larger in people’s thoughts about Mr. Trump than they realize, in part because of the iconic photos taken that day.

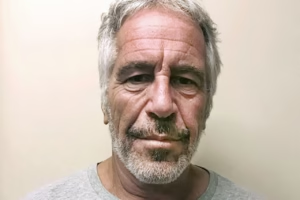

But I think Butler may loom larger in people’s thoughts about Mr. Trump than they realize, in part because of the iconic photos taken that day. Mr. Trump has never spoken of his supporters the way he did this week, with disrespect and baiting insults. On Wednesday on Truth Social, he called the Epstein uproar a Democratic Party “scam” and said “my PAST supporters have bought into this ‘bulls—’ hook, line, and sinker.” Those demanding the government produce all files in the Epstein investigation are ungrateful and don’t deserve him: “I have had more success in 6 months than perhaps any President in our Country’s history. . . . Let these weaklings continue forward and do the Democrats work, don’t even think about talking of our incredible and unprecedented success, because I don’t want their support anymore!” Earlier Mr. Trump told reporters, “I don’t understand why the Jeffrey Epstein case would be of interest to anybody.” “I think, really, only pretty bad people, including fake news, wanna keep something like that going.” In the Oval Office on Wednesday he said he’d “lost a lot of faith in certain people.”

Mr. Trump has never spoken of his supporters the way he did this week, with disrespect and baiting insults. On Wednesday on Truth Social, he called the Epstein uproar a Democratic Party “scam” and said “my PAST supporters have bought into this ‘bulls—’ hook, line, and sinker.” Those demanding the government produce all files in the Epstein investigation are ungrateful and don’t deserve him: “I have had more success in 6 months than perhaps any President in our Country’s history. . . . Let these weaklings continue forward and do the Democrats work, don’t even think about talking of our incredible and unprecedented success, because I don’t want their support anymore!” Earlier Mr. Trump told reporters, “I don’t understand why the Jeffrey Epstein case would be of interest to anybody.” “I think, really, only pretty bad people, including fake news, wanna keep something like that going.” In the Oval Office on Wednesday he said he’d “lost a lot of faith in certain people.”