In a news conference in Ottawa on March 27, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney reacted to developments in what he called “the trade crisis” with the United States.

President Trump, he said, had violated existing trade agreements by imposing on Canada “unjustified” tariffs. “We will respond forcefully. Nothing is off the table.” “We will fight the U.S. tariffs with retaliatory trade actions of our own that will have maximum impact in the United States.” “The road ahead will be long. There is no silver bullet, there is no quick fix.” “But I have every confidence in our country because I understand what President Trump does not: That we love Canada with every fiber of our being.” “The old relationship we had with the United States, based on deepening integration of our economies and tight security and military cooperations, is over.”

Even though it was a week ago, was followed by a telephone call both sides called productive, and has been superseded by this week’s tariff news—Canada isn’t included in the new regime—I can’t get Mr. Carney’s words out of my head. “The old relationship we had . . . is over.” They mark, at the very least rhetorically but not only in that way, the end of an era. And it was a good era.

“How did things ever get so far?” asks Don Corleone in “The Godfather.” “It was so unfortunate, so unnecessary.”

Since Inauguration Day the White House has treated Canada (and other countries—Greenland, Panama—but we’ll stick with Canada) with an attitude of public disrespect. In statements and dealings the president has been offhand, cavalier, belittling. While still prime minister, Justin Trudeau was addressed as “governor.” Canada has been informed it should be our 51st state. This isn’t news, but I want to get to a particular aspect of the story.

It of course matters diplomatically who your allies are, who votes with you in international tribunals, who you can rely on to hear your views with warmth and respect. Regarding Canada it matters also who shares pieces and portions of your heritage, beliefs, past, and shares also the English language. (Winston Churchill always put special emphasis on the importance of who literally speaks your language.) As for our border, Churchill again, in 1939: “That long frontier from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans, guarded only by neighborly respect and honorable obligations, is an example to every country and a pattern for the future of the world.”

But things mattering “diplomatically” is not the only thing. It matters how people, regular citizens, feel about another people nearby, because this helps them situate themselves in the world, understand it, perceive their position. Is that nation next to us our friend? Has it been our friend, can we rely on this?

On Canada a million examples say yes, but my first thought goes to reading in the New York tabloids how the other night in a bar in Manhattan a guy walked in and when they found out he was Canadian they cheered him—drinks on the house. Those stories were all over town. It was the end of January 1980, during the Iran hostage crisis, and news had broken that the Canadian ambassador to Iran, Ken Taylor, had for months and under threat of exposure, hidden American diplomats in his residence in Tehran. Canada’s top immigration official there, John Sheardown, was in on it too. When the Americans first went to him he said, “Hell yes. Of course. Count on us.” (The whole story was famously presented, with license, in the movie “Argo.”)

Later the U.S. Congress struck a gold medal in Taylor’s honor. Its first words, in a nod to Canada’s bilingual tradition, “Entre amis.”

It has always mattered that “our friendly neighbor to the north” was more than a friend and a neighbor.

There was that day in June 1944, in Normandy. We always talk about what the American troops did that day but Canada was there too, storming one of the five invasion beaches, Juno Beach. The 3rd Canadian infantry division took heavy losses but held their beach by day’s end. Maj. David Currie, his South Alberta Regiment isolated and outnumbered, rallied his troops, directed fire, himself took out a German Tiger tank, and walked from the war with a Victoria Cross. For sangfroid there is Doug Hester of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, who remembered being crammed into a landing craft searching for sight of the beach. The din was terrible from artillery and rifle fire; he and the soldier next to him broke into, “The Bells Are Ringing For Me and My Gal.”

You say that’s long ago. Yes, so I guess at this point it’s in their DNA. You say I’m playing your heartstrings. Yes. Heartstrings are history too. You say, well, their trade policies are not completely fair to us. Fine, make them better, work it out. But always show respect, and more. And accept a little—I’m not sure the right word for this but sometimes friends in a slightly inferior financial condition allow friends in a somewhat superior one to pick up the dinner check consistently. Why? They have a little more, you both know it, you’re friends, you would do it for them if roles were reversed, as someday they may be. Friendship supersedes a strict accounting. Tariffs are a form of war and war is always bloody. If they must be imposed it should be done reluctantly and with dignity.

The administration’s roughness is in pursuit of what? Alienation? In what way could that benefit us? We’re becoming a nation of preppers, fearing the fragility of complex systems and seeing the particular talents of our foes. It is odd, at this moment, to alienate the people next door, who have fewer enemies and, in case of hacked grids, lots of electricity.

The new American aggression is a terrible mistake. We are making the world colder. We are making our world colder. And that in time and in ways we don’t anticipate will make us more vulnerable. Which means weaker. In any case it is gross and ignorant to throw old affection away, and to think the only day that counts is today.

I close with March 1986, a White House state dinner for Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney—there would be two in Ronald Reagan’s eight years. Mulroney and his wife Mila had over the years become close friends of the Reagans. The president in his toast called the bond between America and Canada “a treasure.” He urged new agreements to spur prosperity. “Nothing less of course should be expected of two free peoples who live so close.” In his response, Mulroney said he felt he spoke “not only among friends but, in a very real sense, among family.” He urged more liberalized trade. “Friends may sometimes disagree, friends may diverge in opinion, friends speak frankly, but they give each other the benefit of the doubt.“

Nations get into the habit of affection and regard, but the habit takes time to build. It is wicked to break it when it’s already built.

We are not bringing our friends close and our enemies closer. Too bad, when the world looks more and more like a mob war every day. We won’t come away from this new time looking stronger and more commanding but dumber and weaker—less like the Don, more like Fredo.

In August the Soviets erected the Berlin Wall; a year later they put missiles in Cuba. Kennedy’s mastery in the latter crisis, in October 1962, had a reordering effect on his international reputation. Good things followed, including his American University address in which he felt free, having proved himself, having established a more grounded relationship with the Soviet government, to unveil a new plea for nuclear arms control. His speechwriter, the great Ted Sorensen, told me years later that of all the speeches they worked on—the Inaugural Address, the announcement of the missile crisis—the one at American University was the most important.

In August the Soviets erected the Berlin Wall; a year later they put missiles in Cuba. Kennedy’s mastery in the latter crisis, in October 1962, had a reordering effect on his international reputation. Good things followed, including his American University address in which he felt free, having proved himself, having established a more grounded relationship with the Soviet government, to unveil a new plea for nuclear arms control. His speechwriter, the great Ted Sorensen, told me years later that of all the speeches they worked on—the Inaugural Address, the announcement of the missile crisis—the one at American University was the most important.

Three thoughts. One, these aren’t serious people. Two, their job was to show they are an alternative to Mr. Trump, and instead they showed why he won. Third and most important, they will continue to lose for a long time. I hadn’t known that until Tuesday.

Three thoughts. One, these aren’t serious people. Two, their job was to show they are an alternative to Mr. Trump, and instead they showed why he won. Third and most important, they will continue to lose for a long time. I hadn’t known that until Tuesday. “It’s drinking from a fire hose,” the journalist will reply. Meanwhile, normal people are asking: He doesn’t really think he’s a king, right? I’ve grown tired of saying, “Well, that was insane,” and we’re barely a month in.

“It’s drinking from a fire hose,” the journalist will reply. Meanwhile, normal people are asking: He doesn’t really think he’s a king, right? I’ve grown tired of saying, “Well, that was insane,” and we’re barely a month in. But if you go by two things—the temperament of this White House and the ability of its adversaries to launch innumerable cases within all levels of the judicial system—odds are good a crisis will come.

But if you go by two things—the temperament of this White House and the ability of its adversaries to launch innumerable cases within all levels of the judicial system—odds are good a crisis will come.

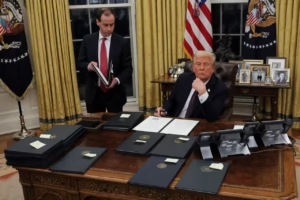

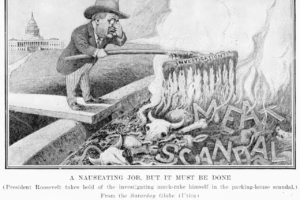

You have to keep this in mind to understand the moment we’re in. Mr. Trump has pierced American consciousness in this way. He has broken through as an instantly recognizable, memeable, cartoonable figure—the hair, the red tie, the mouth—but he also provides, deliberately and not, iconic moments that connect to other iconic moments. The tech barons arrayed behind him as he was sworn in, and the White House meeting hours later in which the president promoted artificial intelligence. As I watched them at the inauguration I abstracted. It was like Elon is passing the solid gold phone to Mark Zuckerberg, who nods and passes it to Jeff Bezos, who passes it to Sam Altman, who marvels at its weight and shine.

You have to keep this in mind to understand the moment we’re in. Mr. Trump has pierced American consciousness in this way. He has broken through as an instantly recognizable, memeable, cartoonable figure—the hair, the red tie, the mouth—but he also provides, deliberately and not, iconic moments that connect to other iconic moments. The tech barons arrayed behind him as he was sworn in, and the White House meeting hours later in which the president promoted artificial intelligence. As I watched them at the inauguration I abstracted. It was like Elon is passing the solid gold phone to Mark Zuckerberg, who nods and passes it to Jeff Bezos, who passes it to Sam Altman, who marvels at its weight and shine.