At the height of its fabled Gilded Age he held a mirror up to America and said, “Not all so pretty, is it?” And the vital, burly citizens of that age peered in and felt shock. It was a distorted mirror, to be sure—the writer who created it was a leftist crusader with the soul of a propagandist—and yet in the reflection one could trace a general outline and detect, too, a florid and emerging disfigurement. I’m overwriting. I’ve just reread Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle,” and its prose, lurid and yet somehow plodding, has worked its way into my mind. But what an important novel it was, what a breakthrough. And it contains a reminder for today.

“The Jungle,” serialized in a socialist journal in 1905 and published in book form the following year, was, famously, an exposé of the harrowing practices of the Chicago-based meatpacking industry. Sinclair went undercover for seven weeks to investigate the Union Stockyards. He presents a teeming city of slums, street urchins and screaming tenement fights between recent immigrants (Poles, Lithuanians, Slovaks) who could barely understand each other’s insults. The soundtrack of their lives was Chicago’s constant hum, “a sound made up of ten thousand little sounds,” which they came to understand was “the distant lowing of ten thousand cattle, the distant grunting of ten thousand swine.”

They worked hard in the stockyards under brutal conditions. In the “chilling rooms” the men contracted rheumatism. The wool pluckers’ hands were ruined by acid. The arms of those who made the tins for canned meat became a maze of infected cuts; their illness was blood poisoning. In summer in the airless, stifling fertilizer mill, phosphates would soak into the workers’ skin, causing headache and nausea. In winter in the “killing beds” the rooms were so cold the animals’ blood froze on the flesh of the workers, who stumbled about like monsters.

There were no worker protections. Unions were shakedown operations for the city’s political machine. In mad pursuit of profits, owners sped up production lines until men broke down, then fired them and hired someone younger and stronger. The workers came to understand they weren’t working for competing companies, it was all “one great firm, the Beef Trust.”

Sinclair meant to indict capitalism’s abuse of innocent men and women who had come to America with dreams in their hearts. Those charges would have political reverberations. But when the revelations came out—advance copies of “The Jungle” had been provided to the wire services and the Hearst newspapers, which front-paged them with howling headlines—the public was most outraged by the unsanitary conditions in which their food was made. (Sinclair said wryly, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”)

The meatpackers “doctored” rotting meat. “It was the custom . . . whenever meat was so spoiled that it could not be used for anything else, either to can it or else to chop it up into sausage.” Tubercular steers, hogs that had died of cholera on the trains—their meat was processed and sold. There was contamination from sawdust and rat dung. Inspectors were paid off.

All this caused a sensation.

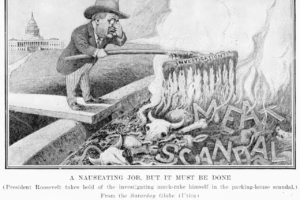

Here enters Teddy Roosevelt, in his second term as president. He’d initially resisted the book: Sinclair was a socialist and a crank. In a letter to William Allen White, TR called Sinclair “hysterical, unbalanced, and untruthful.” But Sinclair had hit a nerve, and Roosevelt conceded some “basis of truth” in the allegations. He sent investigators to Chicago. There was a government probe and report. Congress enacted landmark legislation, the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. The latter expanded the power of a Bureau of Chemistry, which became the Food and Drug Administration.

The whole story—isn’t it something? That they got it right, that it started with a zealot who captured truths others had ignored. That journalism can work as a public benefit, and government make things better.

So now we jump to this moment. Conservatives and Republicans are, as always, impatient with governmental cost, overreach and waste, only more than usual because it’s been a while since these things were any administration’s top priority. In that time, some federal agencies, maybe many, have run wild.

But it’s good to remember now that government employs many people who help us, whom we couldn’t do without. The example always used, justly, is air-traffic controllers. They have to be cool, analytical, know their stuff, or 500 people in a jumbo jet will plunge to their deaths. Those jobs must go only to those who can take the pressure. Food inspection, obviously, is another. Seeing to the proper and safe disposal of nuclear waste. Properly coding Social Security checks.

So many crucial jobs! And it’s helpful to remember they’re usually done well. Their holders must be treated with respect as the professionals they are.

It is also true that the size and scope of government is always growing and requires sharp oversight. The arc of the moral universe is long but bends toward mischief. In our time the political left has grown adept at finding ways to support, employ and give standing to its political allies. They use government to buy off constituencies within their coalitions. That’s how you get the absurdist U.S. Agency for International Development programs Donald Trump and Elon Musk speak of so often. Their existence makes you mad. Which keeps the base stoked. And as all but children know, you can’t do nuthin’ without a stoked base.

But we have to keep our heads straight about what’s important and what’s not. And we can’t demonize government work. Some public servants really are servants.

Internationally, once we won wars and saved people. In the past half century we’ve shifted in big ways to profound generosity. We give food and bandages and help cure diseases. It matters that we are a great and generous nation, and known as such. I asked the leader of a great do-good organization if, in the clinics in South America or Africa, they showed the American flag. Yes, as do the wrappers of the food they give. That is good for us. It matters to have friends in the world. Someday we’ll be in a fix. Someday we’ll need them.

But if you are a taxpayer-funded agency or entity right now, you had better be able to say in a clear, sharp sentence what you do that helps America. Do you protect it from ptomaine poisoning? Do you enhance its reputation in the world? If you can’t produce that clear, sharp sentence, maybe you have a problem. Maybe you aren’t helping. Maybe taxpayers don’t have to pay for you.

It’s good to remember in a time of cutting that not everything is bad, that right-wing propaganda, like left-wing propaganda, often gets carried away, that the libertarian impulse is beautiful but dreamy. A libertarian would have told Upton Sinclair that the market corrects all, that a company that sells bad beef won’t survive long. That’s true. But it’s in the way of things that the rich have the resources to be discerning, and the middle careful, but the poor get sick before the butcher shop shuts down. And we have to take care of each other.