Earlier this week everyone piled on congressional Democrats, or furiously defended them, over the government shutdown and its end. It was the longest in U.S. history, 43 days, and utterly pointless. When it was called I thought of Albert Brooks in “Broadcast News,” who asked, of a different predicament, “Does anybody ever win one of these things?” No, not the administration, not its opponents, not federal employees, not the country. Shutdowns are a trauma without meaning.

All this had me thinking about an aspect of the Democratic Party’s recent divisions. Its main split isn’t only between left and way-left but between those who don’t seem to know why they’re in politics and those who do. The latter are often socialists, who have the advantage of an articulable belief and are driven by it.

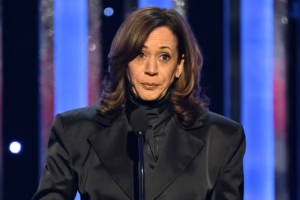

I spent the week reading two memoirs. Kamala Harris’s “107 Days” is about her 2024 presidential campaign. Its title is her defense: She only had 107 days to win, and it wasn’t enough, so she lost. John Fetterman’s “Unfettered,” is about his political life so far. They are strange books in different ways.

In Ms. Harris’s memoir any guiding political philosophy is absent, which is odd in someone who wished to occupy the nation’s highest political office. You should at least go through the motions. Mr. Fetterman does come alive on the subject, but mostly when he’s talking about Republican stands he agrees with.

Ms. Harris’s book is insistently shallow, almost as if that were a virtue, a sign of authenticity. The epigrams she presents at the beginning are weird. There is a quote from an Italian software engineer named Alberto Brandolini: “The amount of energy necessary to refute bull— is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.” The next is from a Kendrick Lamar lyric: “I got loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA.” The former is bitter, the latter bragging, and it’s a rather bitter, bragging book. I think she was trying to signal there will be no intellectual heavy lifting, but do readers need that warning?

She comes alive only over tactics, strategy, how something plays. “The Trump team announced that he would be on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast.” She is interested in media, in how the shot looks and the interview is spun. Her days on the trail begin with “a fifteen-minute briefing on how the campaign was landing in the news.”

She has to “read through important briefing papers before going onstage right after Grammy winner Cardi B.” She worries an election night statement “didn’t have a feel-good line.”

When Joe Biden called to tell her he was dropping out, she pressed for his immediate endorsement. Her argument: She was “the most qualified and ready. The highest name recognition. A powerful donor base.” Also she wouldn’t betray him. She lists no other, more national concerns.

The closest she comes to a political philosophy, a driving force that explains her career, is “I want to keep people safe and help them thrive.” But few enter politics to see constituents endangered and withering. She sees herself as generous in her concern for others—“I’ve always been a protector”—and, again, loyal. But these are personal qualities, not beliefs.

Without realizing it she comes close to a reason for her loss when speaking of illegal immigration. She refuses to call it that, insisting instead on “irregular migration.” She thought new investments south of the border by U.S. companies would stop it.

A revealing anecdote. Shortly before her crucial debate with Donald Trump, Mr. Biden called, she assumed to wish her well. She was in curlers and makeup. He told her some “real powerbrokers in Philly” had told his brother that they weren’t supporting her because she’d been saying “bad things” about the president. He “rattled on”; they rang off. “I just couldn’t understand why he would call me, right now, and make it all about himself. Distracting me with worry about hostile powerbrokers in the biggest city of the most important swing state.” He does seem faintly impaired, or at least like a mean old man.

The head of a party, its presidential candidate, should, in a book, be able to explain her own philosophical beginning points. That she couldn’t or wouldn’t speaks of some of why she lost. But this is also a flaw now with many Democratic office holders of the nonsocialist left.

In John Fetterman’s “Unfettered” you have to infer his political philosophy but he doesn’t make it hard for you. America is a “contradiction,” a place of haves and have-nots; he wants the “struggling” to know they have “an authentic advocate.” He began his political career as a mayor in Western Pennsylvania steel country, with closed-down steel mills and boarded-up Main Streets. He says that since childhood he felt like a loser and became a loner and is drawn to those on the losing end. Government can play a role in helping destroyed small towns come back. He goes deep on his personal experience of depression following a life-threatening stroke and just after his election to the Senate. His portrait of his breakdown is harrowing and believable.

He wanted Bernie Sanders’s endorsement for Senate—“I never shared his support for socialism,” but they “shared some values.” He’s pretty angry. He’s still mad at Mehmet Oz, his Senate opponent, and takes a hard poke at journalists in general and a few in particular. He says he dresses the way he does because he looked like Andre the Giant as a kid, always had trouble finding the right clothes, hates to remember it and now only wears things that are comfortable. This is believable but insufficient: Being grown up carries a price, and part of it is looking like one.

He doesn’t mind talking about where he stands and why, isn’t afraid of big issues, and is most animated when speaking of his nonprogressive views. He stands with Israel, marshals his arguments, smacks those who imply that it “has to do with impaired mental health.”

“I don’t take positions for my own self-interest,” he writes. “I take positions based on what I believe is right.” His stand on Israel has cost him support “from a significant part of my base, and I’m well aware it may cost me my seat. I’m completely at peace with that.”

He broke with Democrats on illegal immigration. “Some in our party assert that an open border is a compassionate policy but I don’t agree. An open border . . . is chaos, both for those immigrants and for those citizens impacted by the overwhelming number of people coming in who need assistance.” At its Biden-era height 300,000 foreigners entered the U.S. illegally in a single month, he says. “That is effectively the city of Pittsburgh showing up every thirty days.”

The Democratic Party, he says, knowingly lied that the border was secure. He believes this was the deciding factor in the 2024 election.

It’s a relief to hear a major political figure speak of at least some of his beliefs and why he holds them. Moderate Democrats should do this more.

Zohran Mamdani knows exactly what he stands for. They’d better, too.