I’m going to say something old-fashioned. It’s a thing we used to say a lot but then we got bored with it or it seemed useless. “We don’t do that.” If we don’t say it we’ll forget it, so we have to keep it front of mind.

President Trump this week gave a speech at Fort Bragg, N.C., to mark the 250th anniversary of the U.S. Army. It wasn’t like a commander in chief addressing the troops, it was more like a Trump rally. The president spoke against a backdrop of dozens of young soldiers who appeared highly enthusiastic. It was as if he was enlisting them to join Team Trump. Presidents always want to convey the impression they have a lot of military support, especially with enlisted men, but the political feel to the event was more overt than in the past. “You think this crowd would have showed up for Biden?” The audience booed the idea.

The president’s language and imagery were unusually violent. For 250 years American soldiers have “smashed foreign empires . . . toppled tyrants and hunted terrorist savages through the very gates of hell.” Threaten the U.S. and “an American soldier will chase you down, crush you and cast you into oblivion.” Sometimes bragging for others is really patronizing them, and sometimes they don’t notice.

The president’s language and imagery were unusually violent. For 250 years American soldiers have “smashed foreign empires . . . toppled tyrants and hunted terrorist savages through the very gates of hell.” Threaten the U.S. and “an American soldier will chase you down, crush you and cast you into oblivion.” Sometimes bragging for others is really patronizing them, and sometimes they don’t notice.

“We only have a country because we first had an army, the army was first,” the president said. No, the Continental Congress came first, authorizing the creation of the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. The next month they chose George Washington to lead it.

The president turned to Los Angeles. “Generations of Army heroes did not shed their blood on distant shores only to watch our country be destroyed by invasion and Third World lawlessness here at home like is happening in California.” “This anarchy will not stand.”

Then to the excellence of his leadership, and to the “big, beautiful bill”: “No tax on tips, think of that.” “Then we had a great election: It was amazing, too big to rig.” “Radical left lunatics.”

He was partisan in the extreme. The troops cheered. Previous presidents knew to be chary with this kind of thing, never to put members of the military in a position where they are pressed or encouraged to show allegiance to one man or party.

We don’t do that. We keep the line clear. In part from a feeling of protectiveness: When you put members of the military in the political crossfire, you lower their stature. People see them as political players, not selfless servants. It depletes the trust in which they’re held.

Earlier in the week the president had sent National Guard troops, and then U.S. Marines, to quell the anti-Immigration and Customs Enforcement lawbreaking in Los Angeles. Naturally in taking such action he’d be at pains to explain his thinking at length, to reassure his fellow citizens that he was doing this solely with the intention of a full restoration of peace to Los Angeles. He’d make clear this isn’t the beginning of, or the regularizing of, a new federal approach to local unrest. There are implications and repercussions to using the national military against Americans on the ground in America.

But there was no such lengthy explanation. The president’s remarks on Los Angeles have been as hot as the Fort Bragg speech. “When they spit, we hit,” he said. That isn’t a warning, it is an excited statement meant to excite: I can’t wait!

We don’t do that. American presidents don’t promise to bloody rioters’ heads. You’re supposed to be reluctant to use force, not eager.

President George H.W. Bush didn’t want to send in the Guard during the 1992 Los Angeles riots. The city had exploded after the acquittal of the four policemen who beat Rodney King. Police were overwhelmed; looting, arson and beatings followed. Sixty-three people were killed, 2,000 injured, 12,000 arrested. The mayor and governor asked for help, and Bush federalized the California National Guard and sent in Marines from Camp Pendleton and soldiers from Fort Ord. The riots began on April 29, and federal troops were getting it under control by May 2. Bush was careful to give a national address explaining his thinking, the facts as he saw them. You do this to show respect for people and their opinions. No one assumed he was taking his action as a first move in some larger, authoritarian plan. Because we knew: We don’t do that.

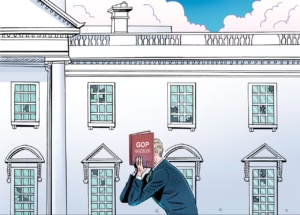

The president has called a big military parade this weekend in Washington to celebrate the Army’s 250th anniversary. It is also the president’s 79th birthday, and he enjoys parades.

Early plans speak of 6,600 soldiers across at least 11 divisions; 150 military vehicles, including 26 M1 Abrams tanks and 27 Bradley Fighting Vehicles. There will be aircraft and howitzers. It all sounds showy, militaristic and braggadocious, the kind of thing the Soviet Union did in its May Day parades, and North Korea still does.

We don’t do that. We don’t have big military parades with shining, gleaming weapons driven through the streets.

Sometimes I wonder of the people around the president: Do they know we don’t do this? Have they read any history? Are they like Silicon Valley tech bros who think history started with them?

Maybe they’re thinking that in a world full of danger it’s good to let Iran and China and the rest know what we’ve got, how our missiles gleam and our soldiers march. But that is just another form of never having read a book. If they had they’d know not only that this isn’t how we do it, but also that we don’t do it that way for a reason.

You want a real show of strength? You never stoop to impress. We are so big and strong we don’t have to show you. You don’t have to see what we’ve got, Mr. Tinpot Dictator, and we don’t have to tell you, because what we’ve got is so big—the miles of missiles, the best-trained, best-dressed troops, the tanks—that if we showed you it would crack the roadway of Constitution Avenue, the concrete would crumble under the weight of our weaponry. So we’re just going to let you imagine what we’ve got in your dreams, your nightmares.

Swaggering threats, parading your strength—we don’t do that, the other guys do that.

Bonus small history: President Bush had scheduled a trip to L.A. around the time of the ’92 riots, and a plan was being cooked up. He was going to give the Medal of Freedom, for a lifetime of entertaining and informing America, to the great and about-to-retire Johnny Carson. Live, on “The Tonight Show,” and they hoped to keep it a surprise. The riots changed the timing and tone of the trip, and Carson was given the medal in a White House ceremony months later. But what a moment that would have been for America, to see the suave and witty man surprised by an honor like that, on the set of his show, from a grateful president who’d come to deliver it personally.

That’s how we do it.

Underlying all this is an air of unusual corruption. I don’t know of any precedent. Charges of influence peddling, access peddling—$TRUMP coins, real-estate deals in foreign countries, cash for dinners with the president, a pardon process involving big fees for access to those in the president’s orbit, $28 million for the first lady to participate in a biographical documentary, the Trump sons’ plan to open a private club in Washington with a reported $500,000 membership fee—those are only some of the items currently known.

Underlying all this is an air of unusual corruption. I don’t know of any precedent. Charges of influence peddling, access peddling—$TRUMP coins, real-estate deals in foreign countries, cash for dinners with the president, a pardon process involving big fees for access to those in the president’s orbit, $28 million for the first lady to participate in a biographical documentary, the Trump sons’ plan to open a private club in Washington with a reported $500,000 membership fee—those are only some of the items currently known.

There are a lot of broken windows in the Trump administration, and Republicans must start doing what grandma would do. She would not just look away.

There are a lot of broken windows in the Trump administration, and Republicans must start doing what grandma would do. She would not just look away.

His own top staffers look as if he made them afraid in a new way. Fear doesn’t solidify relationships.

His own top staffers look as if he made them afraid in a new way. Fear doesn’t solidify relationships.